KARL MARX, the KAWEAH COLONY,

and the FOUNDING of YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK

How Southern Pacific Railroad killed a socialist colony in the Sierras

48 Hills

August 27, 2014

Copyright © 2014 Marc Norton

Thanks to Tim Redmond, editor of 48 Hills, for publishing this article.

I have made some small edits to the published version.

Posted September 10, 2014 (updated September 2016).

There has been considerable hoopla this summer around the 150th anniversary of President Abraham Lincoln putting his signature on the Yosemite Grant Act of 1864. Lincoln set aside Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias for public use and preservation. Yosemite subsequently became a national park in 1890.

Missing from this commemoration are the machinations of corporate power brokers, specifically the Southern Pacific Railroad, in the founding of Yosemite National Park. The very same legislative act that created the park in 1890 also destroyed a socialist experiment in collective living and enterprise – the Kaweah Colony – that had been organized by socialists and labor activists based in San Francisco.

The Kaweah Colony posed a political and economic challenge to the dominance of capital in general, and to Southern Pacific in particular. Thus, at the behest of Southern Pacific, the act that created Yosemite National Park was amended in secret at the last minute to expand the newly created Sequoia National Park, in order to expropriate lands that the Kaweah Colony had settled.

Southern Pacific had its way, and the days of the Kaweah Colony were numbered. The road that the colonists had hacked out of the wilderness with their collective labor was stolen by the park service, without compensation, and served as the main route into Sequoia National Park for decades. The giant sequoia that the Kaweah colonists had named the Karl Marx Tree, by volume the largest known living tree in the world, was renamed the General Sherman Tree. Southern Pacific had its way, and the days of the Kaweah Colony were numbered. The road that the colonists had hacked out of the wilderness with their collective labor was stolen by the park service, without compensation, and served as the main route into Sequoia National Park for decades. The giant sequoia that the Kaweah colonists had named the Karl Marx Tree, by volume the largest known living tree in the world, was renamed the General Sherman Tree.

The power of capital triumphed over the power of the people.

We celebrate the existence of Sequoia National Park, but the fact remains that the park is, in the words of Jay O’Connell, the foremost historian of the Kaweah Colony, “the incidental beneficiary of a giant corporation’s less than benevolent actions.”

FACTORIES IN THE FIELDS

I first learned about the Kaweah Colony a couple of years ago when I picked up and read Carey McWilliams' masterful book, I first learned about the Kaweah Colony a couple of years ago when I picked up and read Carey McWilliams' masterful book,

Factories in the Field. Although I am a lifelong Californian, and not a young one, and have visited Sequoia National Park several times, I had never before heard of the Kaweah Colony.

McWilliams' book is about the development of corporate agriculture and monopoly land ownership in California, and the long history of the struggles of California farm workers. Published in 1939, the book long precedes the formation of the iconic United Farm Workers union of Cesar Chavez fame. The extent of the struggle of farm workers for justice – including Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Indian, Armenian, Portuguese and many other nationalities, as well as Mexican and Latino workers – was an eye-opener even to my jaded vision. The openly terrorist response of the growers, landowners and banks – McWilliams calls it “fascist” – in the early part of the 20th century fully justifies McWilliams' claim that “California is the home of vigilantism.”

As McWilliams wrote in 1939, words as true today as then:

“Today,’ farming’ in its accepted sense can hardly be said to exist in the State. The land is operated by processes which are essentially industrial in character; the importance of finance… has steadily increased as more and more emphasis has been placed on financial control; the ‘farm hand,’ celebrated in our American folklore, has been supplanted by an agricultural proletariat indistinguishable from our industrial proletariat; ownership is represented not by physical possession of the land, but by ownership of corporate stock; farm labor, no longer pastoral in character, punches a time clock, works at piece or hourly wage rates, and lives in a shack or company barracks, and lacks all contact with the real owners of the farm factory on which it is employed.”

The Kaweah Colony was an openly socialist attempt to find an alternative to this system, and despite its initial success, was ruthlessly crushed, as have been many of the struggles of farm workers seeking justice in the fields of agribusiness.

John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath was published in the same year as McWilliams' book. Many saw some sort of conspiracy between Steinbeck and McWilliams, although in fact their books were two completely independent efforts. The Grapes of Wrath has become a classic, while Factories in the Field is all-but forgotten. Perhaps this has something to do with the fact that Steinbeck focused exclusively on white farm workers, the so-called “Okies.” Or perhaps it has something to do with the failure of the labor movement in California to take the struggles of agricultural workers seriously, much less to provide significant material support, despite the fact that agriculture is in many ways the backbone of California’s economy.

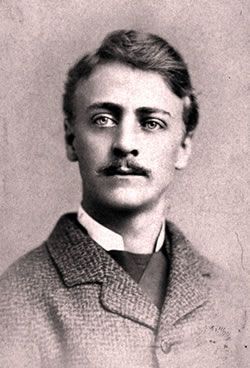

AN ERRATIC GENIUS

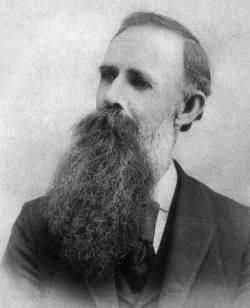

The Kaweah Colony was in large part the brainchild of Burnette Haskell, no relation to “Eddie” Haskell of Leave It To Beaver, although they both exhibited what labor historian Ira B. Cross called “erratic and brilliant genius.”

Haskell was born in 1857 near Downieville in Yuba River country in the Sierras, to parents who had come to California during the Gold Rush. His family moved to San Francisco when he was ten. He showed plenty of smarts, but never graduated high school or the several colleges he attended. Caroline Medan, who wrote a thesis on Haskell, said that his college career was “unduly handicapped by his not registering, not attending class, and not studying.” He spent some time in Chicago driving a streetcar, but returned to San Francisco. He then decided to study law on his own, and managed to pass the bar exam in 1879. Haskell was born in 1857 near Downieville in Yuba River country in the Sierras, to parents who had come to California during the Gold Rush. His family moved to San Francisco when he was ten. He showed plenty of smarts, but never graduated high school or the several colleges he attended. Caroline Medan, who wrote a thesis on Haskell, said that his college career was “unduly handicapped by his not registering, not attending class, and not studying.” He spent some time in Chicago driving a streetcar, but returned to San Francisco. He then decided to study law on his own, and managed to pass the bar exam in 1879.

While Haskell was still searching for his true calling, a rich uncle set him up to run and edit a weekly four-sheet newspaper immodestly called Truth. Haskell soon hooked Truth’s wagon to a labor organization called the Trades Assembly, an early forerunner of today’s Labor Council. Haskell seemed to have found himself at last.

The Trades Assembly was presided over by Frank Roney, a representative from the Seamen’s Protective Union, a self-described “Irish rebel,” an open socialist agitator, and a leader of the racist anti-Chinese agitation of the time.

Haskell was caught up in the whirlwind. He “mastered all the available labor and radical literature and became without a doubt the best read man in the local labor movement,” according to historian Cross.

When the Trades Assembly transformed itself into the League of Deliverance, Haskell went along for the ride. But Haskell also formed his own organizations, first “The Invisible Republic,” then “The Illuminati.” Truth was filled with articles by and about Karl Marx, Victor Hugo, Mikhail Bakunin, Peter Kropotkin and Henry George.

Haskell’s next organizational venture was the International Workingmen’s Association (IWA). The IWA shared its name and inspiration, but nothing else, with Marx’s First International of 1864-1876. According to McWilliams, the IWA “claimed 6,000 members in the western states and a membership of 1,800 in California.” Although those numbers may have been exaggerated, “the IWA had a great deal to do with the revival of the trade union movement in California after its beginnings in the gold rush period,” says McWilliams. Among other initiatives, Haskell and the IWA were involved in the organization of the Coast Seamen’s Union, which later became the Sailors Union of the Pacific.

A statement of the San Francisco IWA principles included:

“The Proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Let therefore the workingmen of all countries unite!… To each according to his needs. From each according to his ability… Educate, Organize, Agitate, Unite. Our Motto: War to the Palace, Peace to the Cottage, Death to Luxurious Idleness. Our Object: The reorganization of Society independent of Priest, King, Capitalist, or Loafer. Our Principles: Every man is entitled to the full product of his own labor, and to his proportionate share of all of the natural advantages of the earth.”

These principles, mixed with study of Laurence Gronlund’s popular 1884 book, Co-operative Commonwealth, and later with Edward Ballamy’s 1888 utopian science fiction novel, Looking Backward: 2000-1887, became the basis for the Kaweah Colony.

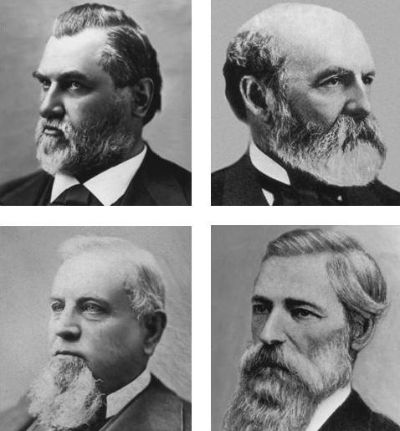

THE SOUTHERN PACIFIC RAILROAD

In the latter part of the 19th century, California politics was dominated by the railroad corporations. In the latter part of the 19th century, California politics was dominated by the railroad corporations.

At the helm were the “Big Four” – Charles Crocker, Mark Hopkins, Collis Huntington and Leland Stanford. These gentlemen, showered with government largesse, created the Central Pacific Railroad and built the western extension of the first transcontinental railroad, completed in 1869. The Central Pacific later merged with the Southern Pacific Railroad.

For decades, California’s economy was dominated by these robber barons. They controlled the state’s transportation system, as well as vast tracts of land. They monopolized the freight and travel industries. They had extensive commercial interests in agriculture, timber and mining.

And they were none too shy about buying political influence. They practically owned the state government and the courts. It was not until 1910, when San Francisco prosecutor Hiram Johnson was elected governor on an anti-Southern Pacific platform, that the power of the railroad corporations was breached.

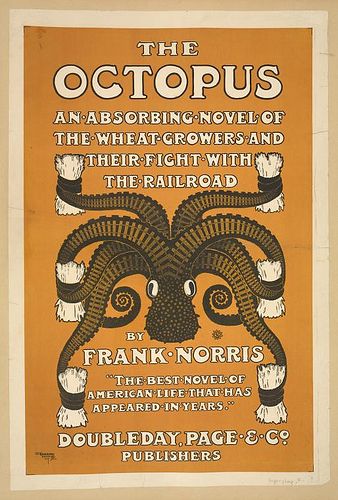

An incident at Mussel Slough defined the era. Some call it a tragedy, some call it a massacre. Five homesteaders died, along with two Southern Pacific gunmen.

Mussel Slough is an area in the Tulare Basin, at the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley, centered around Hanford. Mussel Slough took its name from a slough that went from the Kings River to the now-deceased Tulare Lake. Southern Pacific had been granted tens of thousands of acres in the area as part of the deal with the federal government in return for constructing a rail line.

However, many settlers disputed Southern Pacific’s dealings in the area. Some of the land in Mussel Slough had been settled before Southern Pacific made any plans to build. Many more settlers felt that the company had not fulfilled its obligations under the law regarding where the rail line was to be built, where it was going, and when it was to be built.

Southern Pacific made more enemies when the company tried to sell the land to homesteaders at prices far above what had been advertised when they first moved into the area. The homesteaders created a Settlers’ Land League, and tried to fight the railroad in court, but to no avail, as the courts were bought and paid for by Southern Pacific.

On May 11, 1880, U.S. Marshal Alonzo Poole, a Southern Pacific land agent, and two local settlers who were allies of Southern Pacific rode into the area with the intention of evicting certain homesteaders. But they had not taken into account the fact that the League was holding a rally and picnic at Hanford. Word of the marshal’s presence quickly reached the gathering, and it was not long before the Southern Pacific henchmen found themselves confronted by a much larger group of armed homesteaders. An argument ensued. Somebody started shooting. Stories differ about who started the battle, but before long five homesteaders were dead, along with the two settlers who had ridden with the marshal.

Several of the homesteaders were tried and convicted of resisting a federal officer, but not guilty of conspiring to resist. Although the homesteaders served a few months in jail, many feted them as heroes. The legal battle over the land continued, but Southern Pacific eventually had its way. The story of Mussel Slough was later memorialized in the classic Frank Norris novel, The Octopus: A Story of California. Several of the homesteaders were tried and convicted of resisting a federal officer, but not guilty of conspiring to resist. Although the homesteaders served a few months in jail, many feted them as heroes. The legal battle over the land continued, but Southern Pacific eventually had its way. The story of Mussel Slough was later memorialized in the classic Frank Norris novel, The Octopus: A Story of California.

One interesting name crops up in the Mussel Slough story, that of Daniel K. Zumwalt. Zumwalt was an attorney and land agent for Southern Pacific for 23 years. Zumwalt sent many rounds of letters to Mussel Slough homesteaders demanding that they submit to the railroad’s demands. Zumwalt was lauded for his “ability and management… at the time of the Mussel Slough difficulties” by Professor J. M. Guinn of the Historical Society of Southern California, writing in 1905.

Guinn further reports that Zumwalt, acting as a land agent for Southern Pacific, “sold more land than any other man in Tulare, Kern, Fresno and what is now Kings county.” Zumwalt was a “farmer of considerable means and extensive land holdings,” according to Kathleen Edwards Small, who wrote a History Of Tulare County, published in 1926.

We will meet Zumwalt again and again in our story about the Kaweah Colony.

THE GIANT FOREST

Although Haskell had thrown himself into the socialist camp of the labor movement, he became increasingly dissatisfied with trade unionism as a path to socialism. This was a not unreasonable attitude, especially now that we can look back at the development of the labor movement in the U.S. since the 1880s.

In 1884, Laurence Gronlund published a popular book, The Co-Operative Commonwealth: An Exposition of Modern Socialism. Gronlund, a Danish immigrant to the U.S., addressed his book specifically to Americans, attempted to put socialism on a scientific basis, and argued that creating socialist colonies was “one way to bring a State to the threshold of Socialism.”

Gronlund helped inspire Edward Ballamy’s 1888 utopian science fiction novel, Looking Backward: 2000-1887. By the end of the century, Bellamy’s book reportedly sold more copies than any other book published in the U.S., with the single exception of Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Gronlund’s book attracted Haskell’s attention. Never one to let the grass grow under his feet, Haskell jumped into the colonization movement headfirst. He founded a new organization, the Co-Operative Land Purchase and Colonization Association, and the search was on for someplace to colonize.

One of the members of Haskell’s colonization organization was Charles Keller. He was on a train in 1885, and happened to hear two men discussing “the most magnificent forest of giant redwoods… opened for sale” east of Visalia. Keller investigated, was impressed, and reported what he had learned to Haskell’s colonization group. The game was on.

Here is where Zumwalt’s name pops up again. One of the two men Keller overheard on the train was P. Y. Baker, a civil engineer working in the area. O’Connell, author of the authoritative Co-Operative Dreams: A History of the Kaweah Colony, says that the second man was a surveyor named P. M. Norboe. But Wallace Smith, author of Garden of the Sun: A History of the San Joaquin Valley, says that the second man was none other than Zumwalt. Smith was writing in 1939, O’Connell in 1999. Interestingly, both Norboe and Zumwalt were principals in a land scheme in the Tulare Basin called the 76 Land & Water Company. More on that company later.

The land in question contains immense numbers of pine, fir and cedar trees. It also contains one of the largest stands of giant sequoias in the world. The growing need for lumber in the San Joaquin Valley could provide a ready-made and nearby market, although at the time there were no roads to the forest, and few trails. John Muir had previously visited the area, and claimed to have named it the “Giant Forest,” in homage to the sequoias.

All this land was open to settlement, in accordance with the federal Timber and Stone Act of 1878. But, according to that law, homesteaders could claim no more than 160 acres. That was aimed at preventing monopoly ownership of the land. But the big corporations could play the game, using what came to be known as “dummy entrymen:”

“Foreign sailors arriving in San Francisco, were offered a few dollars, a jug of whiskey, and an evening in a whorehouse in exchange for filing a land claim under the Timber and Stone Act. Before shipping out, these sailors would abdicate title; there were no restrictions on transfer of ownership. Whole redwood forests were acquired in such a manner.”

So wrote Marc Reisner in Cadillac Desert.

So it was no surprise that the authorities took notice when 57 members of Haskell’s association filed land claims in Visalia in October 1885. It did not help that the land was so inaccessible that it was presumed only some corporation with large capital resources could even imagine setting up a timber operation there. Further suspicions were aroused when Haskell’s group “met at the courthouse in Visalia and formed the Tulare Valley and Giant Forest Railroad Company, which might have led suspicious Visalians to believe they were part of a scheme by the despised Southern Pacific to obtain and exploit the forest land,” O’Connell writes.

As a result of these circumstances, the land office suspended the association’s claims until an investigation could determine if they were legitimate. This did not bother Haskell’s crowd much, as they knew very well that they were not fronting for Southern Pacific, but for a socialist enterprise that was its political and economic opposite. They just assumed that their claims would eventually be verified, and the proper deeds granted. Big mistake.

THE KAWEAH COLONY

The colonists plunged ahead. The association boldly solicited homesteaders and financial contributions from all over the world. The association established membership clubs in San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, Denver and elsewhere. Gronlund himself was the head of a club in Boston.

The main work ahead was to construct a wagon road to the forest. The plan to build a railroad was deemed not feasible and put aside, at least for the present. The road could be constructed without the huge capital investment that a railroad would have required. In addition, the colonists could build the road themselves, without having to hire labor.

Construction of the road began in late 1886, and continued for nearly four years. In the end, the colonists spent about $50,000 to build the road, whereas a private contractor would have probably required triple that amount.

The colony established a small tent city in the summer of 1887 on the North Fork of the Kaweah River, called Camp Gronlund by some but eventually named Advance. Members of the association and their families moved in and began work. Many were skilled workers from the trade unions, but there were also artists, musicians and writers, even a few businessmen. The number of colonists varied at any given time, from a low of about 50 to as many as 300. People came to the colony from as far away as England. Membership in the colony cost $500. But a member could put $100 down, and then work off the rest.

Life was not easy in the colony, but there was full employment. Work was organized by department, each with a superintendent. Money was not used in the settlement. Instead, “time checks” were issued, based on the number of hours members actually worked. These time checks could be spent in the community’s store.

There was a Board of Trustees that directed the superintendents, but above all, was the General Meeting. The General Meeting was held monthly, was well attended, and sometimes went on for several days.

There was a school for the children, a library, and an extensive collection of sports equipment. There was a print shop, which published the weekly Kaweah Commonwealth.

There were hay fields, gardens, pastures and fruit trees.

The colony had an early form of socialized medicine. Members did not pay anything for their medical needs. When necessary, a non-resident member who was a doctor and lived nearby would be called to the colony. An experienced matron was available for births.

There were no churches.

The colony never borrowed money, and consequently had no debts.

There was culture. There was an orchestra and a band, and community concerts and dances. Lectures, readings, science classes and book clubs were not uncommon. Picnics, strawberry and blackberry pickings, and camping trips to the Giant Forest were regular occurrences. Swimming and fishing in the Kaweah River were popular pastimes.

And there were disputes. In late 1887, the colony was consumed with a discussion whether to form a corporation or a joint stock company. Haskell advocated for a joint stock company, and when this proposal won the day, a number of members quit the colony, many moving to San Francisco and establishing themselves as the “Democratic Element,” while issuing periodic critiques of the colony.

Much of the written history of the colony focuses on this kind of dissension among the colonists. Anyone who has lived with anyone else knows that problems arise, and are sometimes difficult. Anyone who has attended a “general meeting” knows that things can get out of hand. The critics of the Kaweah Colony often focus on these disputes, and convince many that the whole thing was a bad idea, just as the critics of socialism can focus on its problems and convince many that it is a bad ideology.

But the Kaweah Colony had to create itself out of the human material that was available, not from some imaginary set of perfect human beings. Human beings who have lived their lives in the competitive, decaying system of capitalism can be problematical. Nor is socialism a magic pill that solves all problems. Socialism is a political and economic system for managing problems, having dispensed with the small elite of capitalists who hold all the capital, and thus the power, in their greedy little hands.

THE ROAD

The road that the Kaweah Colony built was the real proof that the colony could have been a success. Stretching 18 miles, the road climbed over 4,000 feet into the untracked forest. It was built by hard labor, using a minimum of dynamite for economic reasons. Yet numerous cuts were made in solid granite in order to keep the road rising on a steady grade.

All this work was done without any capitalist bosses. Nobody made a profit off anybody else’s work. Those who did the engineering and the planning were paid in the same “time checks” as the rest of the workers, and were ultimately responsible to the colony’s General Meeting.

In October 1889, about the time that the road was nearing the timber belt, the Land Office in Washington D.C. sent a special land agent to investigate the still-unresolved land claims. The agent, B. F. Allen, praised the colonists and their work. He called the road a “work of skill and judgment and sense,” and said it was “the best mountain road in the state.” Allen’s report was filed and forgotten.

The next year the Land Office sent another special investigator, Andrew Cauldwell. He also filed a generally favorable report, and said that the colonists had built “the best mountain road I ever traveled over… I cannot help testifying to their industry and perseverance in overcoming almost insurmountable difficulties in building their road.” Cauldwell’s report, like Allen’s, was filed and forgotten.

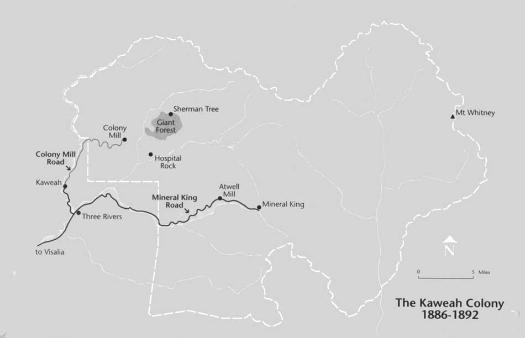

| | Map from Challenge of the Big Trees, by Lary M. Dilsaver and William C. Tweed, 1990 |

In the summer of 1890, the colonists finished constructing their road into the forest. They set up a small mill. Lumber, consisting mostly of pine and fir, started coming down the road.

In the autumn, most of the colonists moved from Advance to the Kaweah town site, south of Advance, in an area that was the center of their agricultural endeavors and had more room for a real town. There the colonists used the lumber they had cut and milled to build a community center with a hall for dining and meetings, a blacksmith shop, a community store, and a barn, among other buildings.

Although the colonists had begun cutting timber, their operation did not look at all like what was happening in other parts of the Sierras. According to Allen’s 1889 report:

“They do not propose to cut and market the timber in its crude state as mere commercial speculators. They have no idea at all of denuding the forest and leaving it a desert of stumps. They propose to first work up the fallen timber then to thin out the thick growth and foster the remainder, to clear the ground of stumps and cultivate and improve the thus opened places.”

Nor did the colonists plan on cutting down any of the giant sequoias. Several miles of rugged canyons separated the sequoias in the Giant Forest from the end of the colony road. In any event, as Haskell wrote in 1889:

“It would be nothing short of vandalism to indiscriminately destroy these sentinels of past centuries, as has been done in several parts of California, by ruthless ravagers of the Competitive system and care will be taken to preserve them in their primitive glory. It is gratifying to know that it is not the intention of this company to sweep from off the face of the earth these grand relics of past centuries. Portions of the forest will be cleared and cultivated, but the ‘Monarchs’ will be left to reign supreme in their grandeur, to excite the awe and admiration of generations yet to come.”

After all, the Kaweah colonists had named the largest living tree in the Giant Forest the Karl Marx Tree. Can anyone really imagine that they would cut the giant Karl Marx Tree down?

SOUTHERN PACIFIC, AGAIN

The Kaweah Colony had its supporters and its detractors, but the completion of their road, and the beginning of timbering focused attention on them in a whole new way. The socialist colony was no longer merely an ideological challenge off in a remote mountain area. No longer were they just tending to their hay fields, gardens, pastures and fruit trees. Now they posed an economic threat as well, as they prepared to bring timber to market.

Lumbering was an enormous industry in the late 19th century. Development in the San Joaquin Valley, immediately adjacent to the Kaweah Colony, was booming, and consequently the need for lumber was immense. Southern Pacific themselves owned large tracts of timberland in California. The railroad certainly had reason to view competitors with concern — and the political clout to do something about it.

In addition to the timber market itself, Southern Pacific made huge profits from freight charges on all the lumber being shipped around the state. If the Kaweah Colony could bring its lumber directly to market in the San Joaquin Valley with little or no use of Southern Pacific’s rail lines, some of those profits from freight charges would also be lost.

Southern Pacific had designs as well on the water that flowed out of the southern Sierras. The Kaweah River flowed into Tulare Lake, along with the Tule River to the south and much of the water from the Kings River to the north. At the time, Tulare Lake was the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi. But Southern Pacific had plans to divert the water in the Kings, Kaweah and Tule rivers in order to irrigate their land holdings in the southern San Joaquin Valley and to flood the corporate coffers with filthy lucre. The Kaweah Colony, upriver from Southern Pacific land holdings, could have been a problem.

Today Tulare Lake is a dry flat plain.

And here we meet Zumwalt once again. Zumwalt and P. Y. Baker were the chief promoters of the 76 Land & Water Company, incorporated in order to divert water from the Kings River and build a canal which, “when completed, will carry a body of water larger than many streams on the Pacific Coast honored with the name of river, and will open up to settlement a large extent of fertile country in Tulare and Fresno counties… There are [no other canals] that will supply so large an extent of country with water for irrigation.” This according to the Pacific Rural Press of 1884. Zumwalt was the company’s secretary, “the principal capital being obtained through his efforts” according to Professor Guinn, and one of the main shareholders.

If the reader recalls, it was P. Y. Baker and his traveling companion who inadvertently tipped off Keller and Haskell’s colonization association about the Giant Forest lands. If the reader recalls, it was P. Y. Baker and his traveling companion who inadvertently tipped off Keller and Haskell’s colonization association about the Giant Forest lands.

The 76 Land & Water Company boasted that they owned 30,000 acres south of the Kings River in the Tulare Basin and Mussel Slough area, “all of which will be watered by their canal.”

In case Zumwalt’s interest in the watershed lands on which the Kaweah Colony sat are not clear, Professor Guinn writes that Zumwalt was “associated with the building of numerous other canals, being a prime mover in the Kaweah Canal & Irrigation Company, in which he was a heavy stockholder, and was deeply interested in legislation to bring about some means whereby the water could not be diverted from the use of the settlers.”

That is, of course, from the use of the settlers to whom Zumwalt and Southern Pacific wanted to sell land and water, not the Kaweah Colony settlers.

It is clear that Zumwalt and his bosses in Southern Pacific had a significant material interest – in land, in water, in timber, and in freight traffic – in preventing the Kaweah Colony from coming into its own.

And so, as we shall see, Southern Pacific was indeed “deeply interested in legislation” that would create Sequoia National Park, and expropriate the Kaweah Colony lands.

THE CONVERSE BASIN

In stark contrast to Southern Pacific and Zumwalt’s interest in preserving the environment of the Giant Forest, the company did not seem to care one wit about preserving the natural environment of Tulare Lake.

But it is Southern Pacific’s lack of interest in preserving the Converse Basin, to the north of the Giant Forest, that really drives the contradiction home. The Converse Basin, centered on the southern slope of the Kings River canyon, was probably the largest and most impressive sequoia grove in the world – before 1890. That was when the cutting began.

Over the next several years an estimated 191 million board feet of lumber was cut. Lumber was floated on the world’s longest flume down the Kings River to Sanger. In the end, gone from the Converse Basin was the General Noble Tree (now called the Chicago Stump), probably the largest sequoia ever cut. Gone also were many sequoias over 2,000 and even 3,000 years in age. Left was the now famous Stump Meadow, containing over 100 sequoia stumps. The devastation of the Converse Basin has been called the most destructive lumbering venture in the history of the world.

Southern Pacific made this possible. Southern Pacific had conveniently built a rail line to Sanger in 1887, about the same time that a couple of shyster San Francisco lumber barons, Hiram Smith and Austin Moore, gained control of the timberland in the Converse Basin, through the Timber and Stone Act and the liberal use of dummy entrymen.

The timber operation in the Converse Basin never made money, because of the high cost of lumbering in this remote area. But Southern Pacific made huge profits from the freight charges on the Converse Basin lumber, and from selling real estate in Sanger.

THE SEQUOIA NATIONAL PARK BILL THE SEQUOIA NATIONAL PARK BILL

While the rape of the Converse Basin was proceeding apace, a movement was growing to protect the sequoias farther south. George Stewart, editor of the Visalia Delta, was the leading voice in this campaign. Born in Placerville, he had become a newspaperman, and had long agitated for preservation of the mountain forests and the giant sequoias.

In the spring of 1889, Stewart helped organize a petition to the Land Office, urging them to not allow the sale of lands in the Grant Grove area. The Grant Grove was (and is) one of the premier sites of giant sequoias in the Sierras, located to the northwest of the Giant Forest and the Kaweah Colony, in what is now Kings Canyon National Park. Zumwalt, among others, was one of the prominent names on the Grant Grove petition.

At about this same time, Stewart learned that there were plans afoot to put another sequoia grove up for sale, the Garfield Grove. The Garfield Grove is also an impressive stand of giant sequoias, at the southern end of what is now Sequoia National Park. Stewart and his allies made a strategic decision to concentrate on agitation for preservation of the Garfield Grove. Unlike other sequoia groves in the area, there were not yet any claims on the land by timber interests or settlers. The Garfield Grove, Stewart argued “is by far the finest sequoia forest still under the undisputed control of the government.”

The plan was to get Congress to establish a “national park,” similar to Yellowstone, the only existing national park at that time, with Garfield Grove at the heart of the new park. Stewart’s Visalia Delta entered into the fray, with headlines that read “Save the Big Trees!” Meanwhile, Congressional representative General William Vandever was recruited to introduce the bill, which he did in July of 1890.

Stewart and his allies deliberately kept the Giant Forest and the Kaweah Colony lands out of the picture. Stewart wrote:

“[N]early all the [other] groves have already passed into private ownership. Certain tracts, like the Giant Forest, that were once on the market and filed on by applicants in good faith, should be restored to the market. This would be nothing more than justice under the circumstances…”

In August and September, Vandever’s Sequoia National Park bill sailed through Congress with little opposition. Opposition was defanged both because of the limited area to be preserved, and public support for the idea that it was time to start protecting the mountain forests. The bill was signed on September 25, 1890, by President Benjamin Harrison, and the U.S. had its second national park.

THE YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK BILL

Parallel to the push for preservation of the Garfield Grove, and far more public, was the campaign to preserve Yosemite. The leading voice here was none other than John Muir.

The Yosemite Grant Act, signed by President Lincoln in 1864 had designated Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias as a preserve, to be administered by the state of California. That is why we are commemorating the 150th anniversary of Yosemite today, in 2014.

In late 1890, Muir published two significant articles in the influential Century Magazine calling for the establishment of a national park in the high country surrounding Yosemite Valley. The model was also Yellowstone, like Stewart’s campaign for a national park to be centered on Garfield Grove.

In March of 1890, Congressman Vandever – yes, the same friend of Zumwalt who a few months later introduced the Sequoia National Park bill – introduced a bill to create a park in the Yosemite area. There has never been a good public explanation of Vandever’s interest in Yosemite. Yosemite was not in his legislative district. Vandever introduced his Yosemite bill months before Muir’s Century Magazine articles. Vandever himself denied he was influenced by Muir or Century Magazine.

One historian opines that Vandever was “probably acting at the request of Southern Pacific officials… [when he] introduced legislation into Congress to create Yosemite National Park.” That is the judgment of Richard Orsi, who in 2005 published Sunset Unlimited: The Southern Pacific Railroad and the Development of the American West, 1850-1930. Orsi’s book is a profoundly sycophantic defense of Southern Pacific, but provides revealing glimpses into the inner workings of the company. One historian opines that Vandever was “probably acting at the request of Southern Pacific officials… [when he] introduced legislation into Congress to create Yosemite National Park.” That is the judgment of Richard Orsi, who in 2005 published Sunset Unlimited: The Southern Pacific Railroad and the Development of the American West, 1850-1930. Orsi’s book is a profoundly sycophantic defense of Southern Pacific, but provides revealing glimpses into the inner workings of the company.

Once Vandever introduced his Yosemite bill, Orsi writes, “the Southern Pacific lobbyists joined in.” Nevertheless, the Yosemite National Park bill did not have smooth sailing, at least at first. It languished in Congress, even while the Sequoia National Park bill sped along. The Yosemite bill was complicated by the large size of the park being proposed and the opposition that engendered.

Indeed, as Congress moved toward a recess on September 30, it looked like the Yosemite bill would have to wait for better days.

And here is where we meet Zumwalt again, for one final apocalyptic moment. Let Orsi tell the story:

“When the Yosemite bill finally came up for consideration in September 1890, Daniel K. Zumwalt, the Southern Pacific’s district land agent for the San Joaquin Valley, was in Washington attending to railroad land-grant business and promoting one of his pet projects, the formation of a national park in the giant-sequoia region, south of Yosemite… [A] devoted lover of wilderness, Zumwalt, through his friend and host in Washington, Congressman Vandever, was instrumental in getting the Yosemite legislation strengthened by enlarging the park beyond even Muir’s initial proposal. Zumwalt also had the bill amended at the last minute to add provisions more than doubling the size of the giant-sequoia park… Vandever and the other floor managers allowed virtually no debate… and the bill passed with few congressmen even comprehending its contents.”

There was no recorded debate on the floor of either the House or the Senate. The amended bill was never printed, contrary to custom. Consequently, few even in Congress knew what they had passed. The President signed the bill the day after it was passed.

It was weeks later that word of the expansion of Sequoia National Park reached the West Coast. There had been no public agitation to increase the size of Sequoia Park. Even Stewart, the leading voice for the creation of the park was taken by surprise.

The kicker? The enlarged Sequoia National Park, created just one week before the passage of the Yosemite bill, now included the Giant Forest, including all of the lands claimed by the Kaweah Colony.

In addition to expanding Sequoia National Park, the amended Yosemite bill created a separate “General Grant National Park” around the Grant Grove.

Orsi continues: Orsi continues:

“Most authorities credit Zumwalt with being the moving force behind both the amendment and the miraculous last-minute passage of the Yosemite-Sequoia bill, although historians have generally misconstrued his actions as motivated by some unspecified corporate greed.”

“Unspecified corporate greed” indeed. Orsi cites sources that are quite specific about the “corporate greed” involved in the expropriation of the Kaweah Colony in Zumwalt’s “last minute” amendment – specifically Southern Pacific’s interest in land, in water, in timber, and in freight traffic – although Orsi can’t bring himself to acknowledge any of this.

Curiously, according to Orsi:

“Zumwalt’s outgoing and incoming correspondence with railroad leaders during his trip and time in Washington is missing from the extensive collection of his papers in the records of the Southern Pacific Land Company in San Francisco. Thus, few details survive of the railroad’s specific interests at that stage of formation of Sequoia National Park.”

The actions of Southern Pacific, and of Zumwalt in particular, in ramming the expropriation of the Kaweah Colony lands through Congress gives new meaning to the concept of railroading a bill through the legislature.

THE KAWEAH COLONY'S LAST DAYS

The Yosemite bill delivered a deathblow to the Kaweah Colony. However, that death did not come easy.

For one thing, the Yosemite bill expressly provided that bona fide claims by private parties on land within the Sequoia National Park boundaries would remain private. The colonists were well liked in the area, and their land claims supported – the settlers had been good neighbors, were a boost to the local economy, and were known for their hard work.

Unfortunately, the federal authorities did not see it that way. Instead, Secretary of the Interior Jon Noble ruled that since the colonists’ claims from 1885 had never been finally validated they had no existing claim on the land, and that the Kaweah Colony’s lands were now under the authority of the new national park. There was no appeal.

To add insult to injury, federal authorities arrested the Kaweah Colony trustees, including Haskell, and charged them with illegally cutting timber on government land. They were dragged to Los Angeles for trial. The jury deliberated all of fifteen minutes, and then returned a verdict of guilty. The four leaders were each fined $301.

A few months later, the trustees were charged with a new crime – the use of the mail to defraud the public by mailing information about the Kaweah Colony and soliciting donations. These charges were so ridiculous that the judge in the trial, Erskine Ross, who had served seven years on the California Supreme Court, ordered the jury to acquit on the grounds of insufficient evidence.

Haskell’s comment on this train of events was simple:

“The machinery of the law was used to take us three hundred miles to meet charges without one single jot of evidence, while gigantic lumber thieves were looting the forests… and the authorities winked their eye.”

Despite the ongoing face-off with federal authorities, the Kaweah Colonists searched for a new way to survive. They secured a legal lease on timberland at Atwell’s Mill on the existing road to Mineral King, and moved their lumber operations there. This land was also in the new Sequoia National Park, but was unambiguously held in private hands and available for timbering.

But even at Atwell’s Mill, where the colony had a clear legal right to log, they were forced into several confrontations with the U.S. Cavalry, which had been sent to the area to protect the park. Fortunately, the cavalry commander, Captain J. H. Dorst, was looking to avoid a fight, and succeeded, despite receiving several illegal orders from Washington to stop the lumber operation at Atwell’s Mill.

Yet the lumber operation did not prove economically successful. The area had already been nearly logged out of pine and fir, and the colonists resorted to logging some of the remaining sequoias. They learned what many lumbermen had already discovered – giant sequoias make poor timber. Cutting them down is very labor-intensive, and as often as not, the wood shatters and splinters when the tree falls. On top of the lack of useable timber, the road was in poor shape, making transport of the lumber difficult. After a few months, the operation was abandoned.

For all intents and purposes, the Kaweah Colony was done for. There was never any real finality to the colony. Many settlers picked up and left, while some stayed and tried to make a go of it on their own. Haskell, disillusioned and bitter, resigned. The Kaweah Commonwealth ceased publication.

With no organization left, various individuals – including both Haskell and Stewart – wrote biting, angry accounts of the inner life of the colony. The mainstream press eagerly picked up on all of this, ignored the real story of the suppression of the Kaweah Colony by the government and their corporate masters, and promulgated a mythical story that the colony had been doomed from the start because, as we all know, socialism just doesn’t work, and we should be happy to put our lives and dreams in the hands of the capitalists.

In later years, there was an attempt to get the federal government to pay the colonists for the road they had built to the forest. That campaign went nowhere although, as noted before, the road continued to be used as the main route into Sequoia National Park for decades. Socialism, they keep telling us, doesn’t work, but the capitalists don’t mind expropriating the property that the collective labor of the people has produced – a lesson that the people of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe learned again a hundred years or so after the demise of the Kaweah Colony.

WHAT DO WE KNOW, AND WHEN DO WE KNOW IT?

Today it’s obvious to all who want to see that the deathblow to the Kaweah Colony – the expropriation of the Kaweah Colony lands in the last-minute amendment of the Yosemite National Park bill – was the work of Southern Pacific Railroad in general and D. K. Zumwalt in particular.

That was pretty well known back in the day, and then forgotten, and then rediscovered.

John Muir himself reported to the Sierra Club in 1896:

“Even the soulless Southern Pacific R. R. Co., never counted on for anything good, helped nobly in pushing the bill for this park through Congress.”

Professor Guinn wrote in 1905 that Zumwalt “enlisted the co-operation of General Vandever... and within two or three days of the adjournment of congress secured the passage of a measure to set aside General Grant Park.” The amendment that created General Grant National Park, of course, was the same amendment that expanded Sequoia National Park to include the Kaweah Colony lands.

The History of Tulare and Kings Counties, published in 1913 by Eugene Menefee and Fred Dodge, repeats the statement that Zumwalt got Vandever on board and “secured the passage of an authorization of the setting aside of General Grant Park.”

And in The History of Tulare County, published in 1926, Kathleen Edwards Small wrote:

“Another bill providing for the creation of the Yosemite National Park and extending the boundaries of Sequoia National Park was introduced. D. K. Zumwalt of Visalia, who had been interested in the preservation of the General Grant Grove, was then visiting General Vandever in Washington and it was at his instigation that this tract was included in the bill as a separate park, unanimous consent to the amendment being secured by General Vandever.”

Despite all this, in 1916 Stewart, now an old man growing somewhat forgetful, embarked on a personal search to discover who had been responsible for the amendment to the Yosemite bill. His first suspect was one Gustavus Eisen, a botanist who had worked with the California Academy of Sciences. It took five years of correspondence between the two to establish to Stewart’s satisfaction that Eisen was not the one Stewart was searching for.

Oscar Berland, who wrote an important article about the Kaweah Colony in 1962 for the Sierra Club Bulletin, continues the story:

“Stewart continued his search. He collected copies of relevant government documents, but apparently they too offered no answer. Late in 1930 he addressed the question to Robert Underwood Johnson [the editor of Century Magazine].

“Stewart was now 73; the park was 40. The problem of the Giant Forest’s reservation was still unsolved. For years it had been assumed that Stewart, now acclaimed the parks ‘father,’ had been responsible for the protection of the park’s heart. By this time even Stewart had come to believe that the original bill had somehow reserved the forest and that the second had merely added untimbered sections…

“‘I did not learn at the time why or at whose suggestion the Park was enlarged,’ he wrote Johnson. ‘I inquired later of John Muir and others to whom he referred me, but no one of whom inquiry was made could throw any light on the matter.’

"…A few months later George W. Stewart, who had protected the park for forty-one years, took with him to his grave the disturbing puzzle of its establishment.”

In fact there really was no puzzle, except to those who were confused by Stewart’s erratic investigation and the willingness of Southern Pacific to hide in plain sight. But, as histories of the Yosemite, Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks began to be written for mass consumption, it just became de rigueur to sloppily tell the story without ruffling the feathers of the corporate puppet masters.

THE KARL MARX TREE

The story about the naming of the Karl Marx Tree, now more popularly known as the General Sherman Tree, is instructive about how history gets made.

As previously noted, the Karl Marx Tree in the Giant Forest is, by volume, the largest known living tree in the world. The Kaweah Colonists didn’t know that, but they knew it was big. And so they named it after a big man that was an inspiration to them.

According to Wallace Smith, who has already been introduced to us as the author of the 1939 history of the San Joaquin Valley Garden of the Sun, it was Charles Keller, who first tipped off the colonization association about the Giant Forest, who “named the biggest tree in the forest after the man whom they most revered… This name the tree retained until the government authorities re-named it the General Sherman.”

It is no surprise that the “government authorities” would rename the Karl Marx Tree. And General Sherman, while not universally loved south of the Mason-Dixon line, certainly was a big man in his own right.

But this storyline was not quite good enough for some people. It seems a little crass that the government would rename a tree just because they weren’t fond of the man it was named after. Somehow the story got spread around that it was the Kaweah Colonists who had renamed the tree – that it had originally been the General Sherman Tree until the socialists decided to honor Karl Marx. And thus, the story goes, the government authorities simply restored the tree’s original name after the demise of the Kaweah Colony.

But then, how to explain how the General Sherman Tree got its name in the first place? The story is that the tree was named by one James Wolverton. Wolverton was a trapper and cattleman who worked in the Giant Forest for a time, and had served under General William Tecumseh Sherman. There is even a date that Wolverton named it – August 7, 1879. I think it would be a safe bet that Wolverton would be a complete unknown if it were not for the claim that he named this particular Big Tree.

But where did the Wolverton story come from? I put this question to the Sequoia Natural History Association which sells a pamphlet called – surprise, surprise – The General Sherman Tree, which repeats the Wolverton story. I got an answer from the author of that pamphlet, William Tweed, also the co-author with Lary Dilsaver of the authoritative Challenge of the Big Trees of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. Tweed wrote to me to say:

“The official story… is that it was given the general’s name by James Wolverton on August 7, 1879… Unfortunately, there is no original source for this fact. I can trace it back in print to Ansel Hall’s 1921 Guide to the Giant Forest… but have found nothing earlier that is so specific. Certainly, the General Sherman name was in use earlier than that. Park files contain many early references to the tree including photographs that show the name affixed to the tree. All of these are after 1890, however, when the park was created.

“This leads us to the critical question – What contemporary evidence do we have that the tree in question was named for General Sherman before it was called ‘Karl Marx?’ The answer, unfortunately, is that I have never found anything from the period 1879-1885 that uses the ‘General Sherman’ name… I will not claim to have made a full reading of the newspaper articles of that time that captured the accounts of trips into the Sierra.

“Traditionally, the best source for early park history is Walter Fry, the park’s first civilian superintendent and a resident of the park region for half a century. Fry interviewed many early park pioneers (including Hale Tharp) [Wolverton worked for Tharp] and captured their stories... Nowhere in his writings, however, can I find the August 7, 1879 story.

“All of this, to be honest, makes me a little suspicious. The date is way too specific, among other things. Why would a cowboy remember the exact date on which he first encountered a tree?”

Tweed ends this with the simple statement that the truth of the matter is “Your call.”

THE MAP

So for decades now the Karl Marx Tree has been called the General Sherman Tree, and the “official story” about the expropriation of the Kaweah Colony is that nobody knows who did it.

Then along came Oscar Berland. Berland was a young San Francisco radical, back in the 1960s that is, who aspired to write a history of the Kaweah Colony. He never completed that history, or at least never published one. But he did write an article in 1962 for the Sierra Club Bulletin about his investigation entitled Giant Forest’s Reservation: The Legend and the Mystery.

Berland did some serious investigation, and uncovered a Southern Pacific map, which shows the new boundaries of Sequoia National Park, as delineated in the Yosemite National Park bill, dated October 10, 1890.

“On that date,” Berland writes “neither the colonists, the local conservationists, nor the California press were yet aware of the park’s enlargement. Congressional documents not excepted, this is the earliest reference to Sequoia Park’s enlarged boundaries extant!”

With this revelation, Southern Pacific reentered the lexicon of those who want to tell the story of the founding of Sequoia National Park.

Years later, when Orsi wrote his ode to Southern Pacific, he acknowledged that the October 10 map was “based on precise information provided by Zumwalt.”

Thank you, Oscar.

AND THANK YOU, KARL MARX

The story of the Kaweah Colony is not just the story of its suppression. It is also the story of its meaning.

Since the colonists sought to honor Karl Marx, it is only fair to check in with Marx to see what he has to say about their movement. This, from Marx’s Inaugural Address to the Working Men’s International Association, in 1864:

“We speak of the co-operative movement… The value of these great social experiments cannot be over-rated. By deed, instead of by argument, they have shown that production on a large scale, and in accord with the behests of modern science, may be carried on without the existence of a class of masters employing a class of hands; that to bear fruit, the means of labour need not be monopolized as a means of dominion over, and of extortion against, the labouring man himself; and that, like slave labour, like serf labour, hired labour is but a transitory and inferior form, destined to disappear before the associated labour plying its toil with a willing hand, a ready mind, and a joyous heart…”

The Kaweah Colony proved once again, more than 20 years after Marx spoke these words, that workers can build a life for themselves without “a class of masters employing a class of hands.”

But there is another lesson here, as Marx went on to say in his speech:

“At the same time, the experience of the period from 1848 to 1864 has proved beyond doubt that, however excellent in principle, and however useful in practice, co-operative labour, if kept within the narrow circle of the casual efforts of private workmen, will never be able to arrest the growth in geometrical progression of monopoly, to free the masses, nor even to perceptibly lighten the burden of their miseries… To save the industrious masses, co-operative labour ought to be fostered by national means. Yet the lords of the land and the lords of capital will always use their political privileges for the defence and perpetuation of their economical monopolies…”

“To conquer political power has therefore become the great duty of the working classes.”

Today, at the end of the road into Cedar Grove in Kings Canyon is a beautiful, green meadow, surrounded by Yosemite-like cliffs of granite. This is Zumwalt Meadow.

This meadow is named after Zumwalt because he once owned the meadow. How did this man come to own this place? For that matter, how did Southern Pacific and a conglomerate of corporate marauders come to be the power-brokers of the earth, who can ruin a beautiful enterprise like the Kaweah Colony, who can destroy the Converse Basin, who can stretch death-and-destruction on rails from one end of this land to the other? Can their bloody hands be cleansed by the gift of a few plots of land for public use?

“To conquer political power has therefore become the great duty of the working classes.”

_____________________________________________________________________________

Selected Sources:

Berland, Oscar –

Giant Forest’s Reservation: The Legend and the Mystery

(Sierra Club Bulletin, December 1962)

Brown, J. L. –

The Mussel Slough Tragedy (1958)

Cross, Ira B. –

History of the Labor Movement in California (1935)

Dilsaver, Lary M. and William C. Tweed –

Challenge of the Big Trees of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks (1990)

Guinn, Prof. J. M. –

History of the State of California and Biographical Record of the San Joaquin Valley, California (1905)

Hine, Robert V. –

California’s Utopian Colonies (1953)

Jones, Holway R. –

John Muir and the Sierra Club: The Battle for Yosemite (1965)

Menefee, Eugene L. and Fred A. Dodge –

History of Tulare and Kings Counties (1913)

McWilliams, Carey –

Factories in the Field (1939)

O’Connell, Jay –

Co-Operative Dreams: A History of the Kaweah Colony (1999)

Orsi, Richard J. –

Sunset Limited: The Southern Pacific Railroad and the Development of the American West, 1850-1930 (2005)

Small, Kathleen Edwards –

History of Tulare County (1926)

Smith, Wallace –

Garden of the Sun: A History of the San Joaquin Valley, 1772-1939 (1939)

Strong, Douglas Hillman –

Trees or Timber? The Story of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks (1968)

Tweed, William –

Kaweah Remembered (1986)

Tweed, William –

The General Sherman Tree (1988)

Willard, Dwight –

A Guide to the Sequoia Groves of California (2000)

|