JACKIE ROBINSON: "I Never Had It Made"

Z Magazine (September 2013)

Beyond Chron (November 2013)

Copyright © 2013 Marc Norton

I have made some revisions

from the published version.

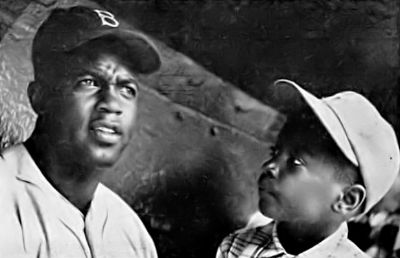

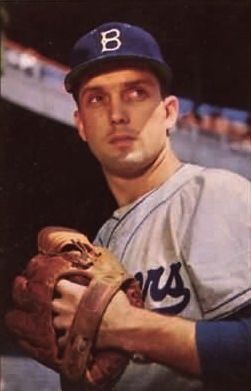

Brian Helgeland, the writer and director of 42, the most recent film to tell the story of Jackie Robinson, cuts the movie at the end of Robinson’s first season with the Brooklyn Dodgers, in 1947.

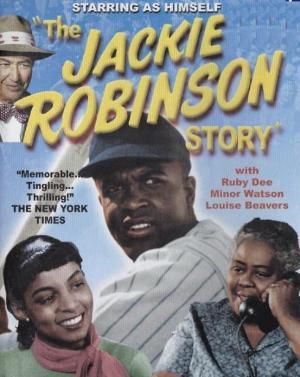

But The Jackie Robinson Story, released in 1950, the first feature film about Robinson — and having the advantage of starring Robinson playing himself — ends with Robinson testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in Washington DC.

“I know that life in these United States can be mighty tough for people who are a little different from the majority,” Robinson says, in a recap of his actual appearance before HUAC in 1949. “I’m not fooled because I’ve had a chance open to very few Negro Americans. But I do know that democracy works for those who are willing to fight for it, and I’m sure it’s worth defending. I can’t speak for any 15 million people, no one person can, but I’m certain that I, and other Americans of many races and faiths, have too much invested in our country’s welfare to throw it away, or to let it be taken from us.” “I know that life in these United States can be mighty tough for people who are a little different from the majority,” Robinson says, in a recap of his actual appearance before HUAC in 1949. “I’m not fooled because I’ve had a chance open to very few Negro Americans. But I do know that democracy works for those who are willing to fight for it, and I’m sure it’s worth defending. I can’t speak for any 15 million people, no one person can, but I’m certain that I, and other Americans of many races and faiths, have too much invested in our country’s welfare to throw it away, or to let it be taken from us.”

To today’s audience, this testimony sounds like standard patriotic rhetoric, not much different than the ritual singing of the "Star Spangled Banner" before a ball game.

But to a 1950 audience, in the early days of what came to be known as the McCarthy era, this was an unmistakable bow to the war-mongering, anti-communist and anti-Soviet hysteria of the time. It was also a thinly veiled attack on Paul Robeson, then the most famous Negro American in the world, renowned as a singer, actor and athlete — and an untiring fighter for social and economic justice for African Americans, including the integration of baseball.

Robeson had famously declared, at the Paris Peace Conference in 1949, “We shall not make war on anyone. We shall not make war on the Soviet Union…. We shall support peace and friendship among all nations…” This is what had earned Robeson the ire of HUAC and caused them to summon Robinson to testify before the committee. Robeson had famously declared, at the Paris Peace Conference in 1949, “We shall not make war on anyone. We shall not make war on the Soviet Union…. We shall support peace and friendship among all nations…” This is what had earned Robeson the ire of HUAC and caused them to summon Robinson to testify before the committee.

Years later, Muhammad Ali expressed much the same sentiment as Robeson, though somewhat more pithily, when he proclaimed, “No Viet Cong ever called me nigger.”

Less than a month after the release of The Jackie Robinson Story, troops of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea launched an attack on the U.S.-backed puppet government in the south, civil war was raging in Korea, and the question of the willingness of African Americans, indeed of all Americans, to fight in defense of “democracy” was of paramount importance.

Robinson would come to regret his testimony before HUAC.

TROUBLE AHEAD, TROUBLE BEHIND

Helgeland wisely leaves the HUAC hearing out of 42, although he does include a lengthy rendition of the Star Spangled Banner on the day Robinson debuted for the Dodgers at Ebbets Field, on April 15, 1947.

The HUAC hearing is not all Helgeland leaves out. 42 essentially begins in 1945 when Branch Rickey — the President, General Manager and part owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers — recruited Robinson. As a result, so much of the historical context is missing that the initiative to integrate baseball seems to have come full-blown out of the head of Branch Rickey. The HUAC hearing is not all Helgeland leaves out. 42 essentially begins in 1945 when Branch Rickey — the President, General Manager and part owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers — recruited Robinson. As a result, so much of the historical context is missing that the initiative to integrate baseball seems to have come full-blown out of the head of Branch Rickey.

Rickey deserves his due for courage and tactical genius, but 42 lacks any acknowledgment of the years of struggle against segregation in general and against the magnates of baseball in particular, which created the ground on which Rickey could fight.

For example, in 42, we meet Wendell Smith, a Black sportswriter for the Pittsburgh Courier, but learn little about him. In reality, Smith had been writing about Jim Crow baseball for years, starting with a groundbreaking series of articles in 1939. For example, in 42, we meet Wendell Smith, a Black sportswriter for the Pittsburgh Courier, but learn little about him. In reality, Smith had been writing about Jim Crow baseball for years, starting with a groundbreaking series of articles in 1939.

Smith was not alone in this crusade, but was joined by others in the Black press, like Frank Young of the Chicago Defender, Sam Lacy of the Baltimore Afro-American and Joe Bostic of the Harlem People’s Voice. The long campaign by the Black press against segregated baseball does not makes its way into 42.

And we certainly do not see or hear anything in the film about the unremitting campaign of the Communist Party to desegregate baseball, despite the fact that, as acknowledged by Arnold Rampersad in his authoritative Jackie Robinson, A Biography, “the most vigorous efforts came from the Communist press, including picketing, petitions, and unrelenting pressure for about ten years in the Daily Worker, notably from Lester Rodney and Bill Mardo.” The Daily Worker was the Communist Party newspaper, based in New York. And we certainly do not see or hear anything in the film about the unremitting campaign of the Communist Party to desegregate baseball, despite the fact that, as acknowledged by Arnold Rampersad in his authoritative Jackie Robinson, A Biography, “the most vigorous efforts came from the Communist press, including picketing, petitions, and unrelenting pressure for about ten years in the Daily Worker, notably from Lester Rodney and Bill Mardo.” The Daily Worker was the Communist Party newspaper, based in New York.

Nor, in 42, do we hear or see anything about the Committee to End Jim Crow in Baseball, launched in 1940 by the New York Trade Union Athletic Association (TUAA). The TUAA, with over 300,000 members, organized sports programs for union members. The Committee to End Jim Crow in Baseball also included college sports editors from Columbia University, New York University (NYU), City College of New York (CCNY), Brooklyn College, and St. John’s University.

On July 7, 1940, the TUAA officially took over the New York World’s Fair Stadium for a labor sports carnival, made the theme for the day “Ending Jim Crow in Baseball,” sponsored baseball games between racially-mixed teams, and collected more than 10,000 signatures on a petition against segregated ball.

Both Rodney and Mardo report that by 1942 the Commissioner of Baseball, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, had more than one million signatures on his desk. In that same year, the Greater New York Industrial Union Council, representing over a half million Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) union members, unanimously passed a resolution to “end jim-crow in the big league baseball now.”

42 also tells us nothing about the delegation of Black publishers that Paul Robeson took to the annual winter meeting of major league baseball team owners in 1943. Robeson’s history as an outstanding All-American college football player was well known, as well as his struggle against discrimination when he joined Rutgers’ all-white team in 1915. “I was almost killed the first year,” he told the team owners.

Commissioner Landis presided over the meeting at the Roosevelt Hotel. Landis, one of the chief enforcers of the ban against Black players, had lied to the press the year before, claiming that, “Negroes are not barred from organized baseball… and never have been in the 21 years I have served.” Commissioner Landis presided over the meeting at the Roosevelt Hotel. Landis, one of the chief enforcers of the ban against Black players, had lied to the press the year before, claiming that, “Negroes are not barred from organized baseball… and never have been in the 21 years I have served.”

Introducing Robeson at the meeting, Landis said, “Everybody knows him or what he’s done as an athlete and an artist…

“I want to make it clear that there is not, never has been, and as long as I am connected with baseball, there never will be any agreement among the teams or between any two teams, preventing Negroes from participating in organized baseball. Each manager is free to choose players regardless of race, color, or any other condition.”

Robeson then proceeded to urge the magnates to integrate the game and that “action be taken this very season.” It didn’t happen that way. Landis had to die first, after a heart attack in November 1944. Subsequently, Albert Benjamin “Happy” Chandler was appointed Commissioner. And that’s about where 42 starts. Robeson then proceeded to urge the magnates to integrate the game and that “action be taken this very season.” It didn’t happen that way. Landis had to die first, after a heart attack in November 1944. Subsequently, Albert Benjamin “Happy” Chandler was appointed Commissioner. And that’s about where 42 starts.

Years later, it was learned that the FBI had monitored the 1943 baseball owners meeting. A report to

J. Edgar Hoover read:

“Pressure is being exerted for the purpose of lifting the ban upon Negro players participating in organized ball…. All of these individuals have been reliably reported as members of the Communist Party.”

And thus practically written out of history, both textbook and cinematic.

BASEBALL IS ABOUT GREEN, NOT BLACK AND WHITE

Rickey exhibited no inclination to integrate baseball during his 25 years as an executive with the St. Louis Cardinals. Even after he moved north and took over the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1942, he showed no outward sign of interest in recruiting Black players.

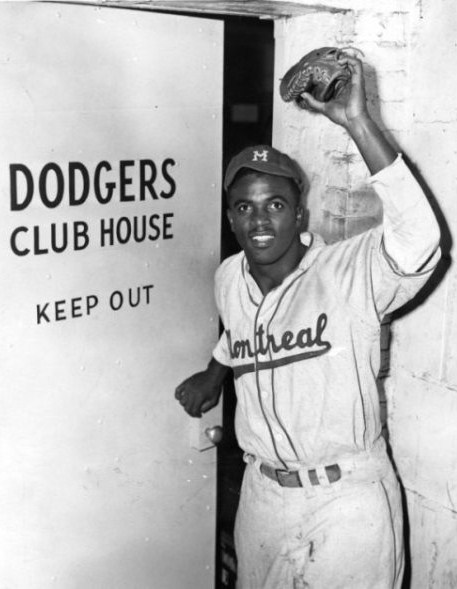

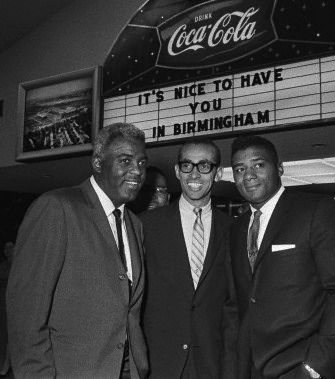

When Joe Bostic of Harlem’s People’s Voice and Nat Low of the Daily Worker showed up unannounced at the Dodger preseason camp in April 1945 with two Negro League players, pitcher Terris McDuffie and first baseman Dave Thomas, asking to let them try out, Rickey flew into a rage for being put on the spot. He allowed McDuffie and Thomas on the field for about 45 minutes, then summarily dismissed them.

From left: Nat Low, Dave Thomas, Terris McDuffie, Joe Bostic

Rickey never spoke to Bostic again. A month later he called a press conference and denounced much of the agitation to integrate baseball as communist-inspired. At this point, no one could have guessed that Rickey was concocting a plan to integrate the game.

At his press conference, Rickey also proclaimed that the existing Negro Leagues were nothing more than “rackets” and announced a plan to create a new circuit for Black players, which he named the United States League. Of course, the Negro Leagues were no more a racket than Major League Baseball. But the United States League proved to be the biggest racket of all. The new organization never held a game. It did, however, provide cover for Rickey to send scouts out for Black baseball players to Negro League games without tipping his hand about his real intentions.

The Negro Leagues were a known quantity to Major League Baseball magnates. Many of the Black teams played in white-owned stadiums, including Yankee Stadium, paying substantial rent money. Some of the Black teams had white owners. Almost all of the booking agents, who skimmed up to 40% of the gross receipts off the top, were white. While most Negro League players had their eyes on the majors, the Negro League owners and agents had everything to lose if baseball were to be integrated, which would surely lead to the collapse of the Negro Leagues. But Rickey had no stake in the Negro Leagues, any more than he did in his make-believe United States League.

The economic imperatives pushing Rickey toward integration are not complex. Bringing Black talent onto the Dodgers would potentially give them an edge in winning games, pennants and maybe even a World Series or two — as it did. Winning meant money. Bringing Black fans into the stadiums would also mean more money.

Early on in 42 Rickey lays it on the line. “Dollars aren’t black and white, they’re green.” Robinson says much the same thing in his autobiography: “Money is America’s God, and business people can dig black power if it coincides with green power.” Baseball may be America's pastime, but business is America's heart and soul.

In the world of 42, the main pillars of segregation are ignorant managers, redneck players, and racist fans. The owners are largely invisible, but they were then, as now, the ones calling the shots. Most owners feared that a flood of Black fans would mean white flight from the stadiums, especially in the South. That didn’t mean money, it meant ruin. The owners’ lust for profits was key, not their fear of Blacks in the shower rooms.

“The most prejudiced of the club owners were not as upset about the game being contaminated by black players as they were by fearing that integration would hurt them in their pocketbooks,” Robinson writes. “Once they found out that more — not fewer — customers, black and white, were coming through those turnstiles, their prejudices were suppressed.”

Rickey, smarter than most of the owners, had the wisdom to see that integration was going to happen in baseball sooner or later. This was easier to see in New York. Rickey, smarter than most of the owners, had the wisdom to see that integration was going to happen in baseball sooner or later. This was easier to see in New York.

It wasn’t just the agitation around integrating baseball, much of which was centered there. When a New York cop shot a Black soldier at the Hotel Braddock in 1943, Harlem exploded, an uprising later memorialized by James Baldwin in Notes of a Native Son. Black soldiers were dying in Europe and the Pacific. They weren’t going to be overseas forever. Times were changing.

Rickey was a man to ride the tiger, not wait for it to attack him. Why not be the first to integrate baseball and reap the economic rewards that would bring?

In a later scene in 42, Rickey and Robinson are alone in a locker room, Robinson having just been stitched up after being spiked in the leg. Robinson asks Rickey to tell him why he is doing this.

Rickey’s first reply is, “We had a victory over fascism in Germany. Time we had a victory over racism at home.”

“No, why?” Robinson demands. “Why’d you do it? Come on. Tell me.”

Rickey pauses, then tells Robinson: Rickey pauses, then tells Robinson:

“I love this game. I love baseball. Given my whole life to it. Forty odd years ago I was a player/coach in Ohio, Wesleyan University. We had a Negro catcher, best hitter on the team, Charlie Thomas, fine young man. Saw him laid low, broken, because of the color of his skin, and I didn’t do enough to help. Told myself I did, but I didn’t. There is something unfair at the heart of the game I love and I ignored it.”

The real Rickey told the story about Thomas many times. One can credit him with having a higher purpose here than cold cash or not. But integration would only work for the Dodgers, or any other team, if it penciled out green. Fortunately for justice, it did.

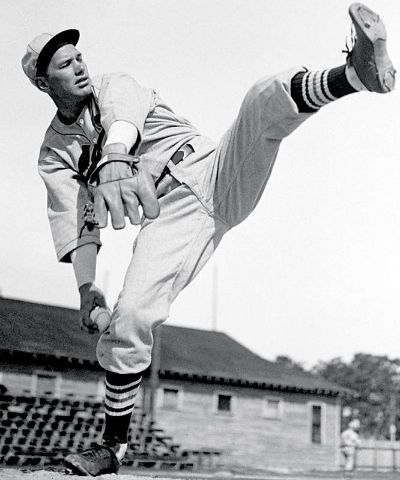

Rickey was certainly right about there being “something unfair at the heart of the game.” But there is more unfairness at the heart of the game than racism, as vile as that is. As Dizzy Dean, a lifetime 150-83 pitcher for the St. Louis Cardinals and Chicago Cubs, once told a group of ballplayers in Indianapolis in 1948:

“Don’t forget the boss is settin’ back there computin’ the dough as it rolls in. He’s makin’ money and plenty of it. That’s about all he thinks about… “Don’t forget the boss is settin’ back there computin’ the dough as it rolls in. He’s makin’ money and plenty of it. That’s about all he thinks about…

“The time will come when you can’t throw and run and hit like you do now. But the owners will still be makin’ dough. There ain’t no age limit on that. Take a tip from ol’ Diz.”

Rickey is often credited with saying:

“I’m a man of some intelligence. I’ve had some education, passed the bar, practiced law. I’ve been a teacher and I deal with men of substance; statesmen, business leaders, the clergy...

So why do I spend my time arguing with Dizzy Dean?”

Don’t argue with Dizzy. He had baseball down cold.

ROBINSON'S “EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION”

In 1949, Rickey released Robinson from his vow not to fight back. Robinson quotes Rickey in his autobiography: “I realized the point would come when… Jackie would break with ill feeling if I did not issue an emancipation proclamation for him. I could see how the tensions had built up in two years and that this young man had come through with courage far beyond what I asked, yet, I knew that burning inside him was the same pride and determination that burned inside those Negro slaves a century earlier… So I told Robinson that he was on his own. Then I sat back happily, knowing that, with the restraints removed, Robinson was going to show the National League a thing or two.”

Robinson did indeed show the world a thing or two. He helped lead the Dodgers to six pennants and a World Series Championship. He was a National League All-Star every year from 1949 to 1954. He was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962, the first year of his eligibility.

But Robinson also “made enemies,” wrote Dick Young, a sportswriter for the New York Daily News. “He has a talent for it. He has the tact of a child because he has the moral purity of a child.”

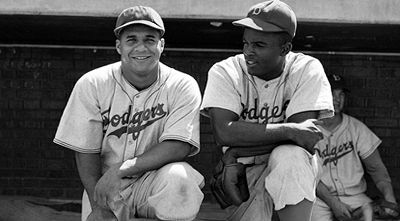

Rickey had been right when he told Robinson that when he fought back, many would only see Robinson’s blows, not the blows that had been inflicted on him. Robinson had many quarrels with umpires, who often gave him much less slack than they would have given a white player. Sportswriters tried to fan the flames of discord between Robinson and Roy Campanella, the Black catcher who joined the Dodgers in 1948, claiming that “Campy” was unhappy with Robinson’s allegedly quarrelsome conduct. Robinson also lodged complaints about Jim Crow hotel arrangements, notably calling out the Chase Hotel in St. Louis. Rickey had been right when he told Robinson that when he fought back, many would only see Robinson’s blows, not the blows that had been inflicted on him. Robinson had many quarrels with umpires, who often gave him much less slack than they would have given a white player. Sportswriters tried to fan the flames of discord between Robinson and Roy Campanella, the Black catcher who joined the Dodgers in 1948, claiming that “Campy” was unhappy with Robinson’s allegedly quarrelsome conduct. Robinson also lodged complaints about Jim Crow hotel arrangements, notably calling out the Chase Hotel in St. Louis.

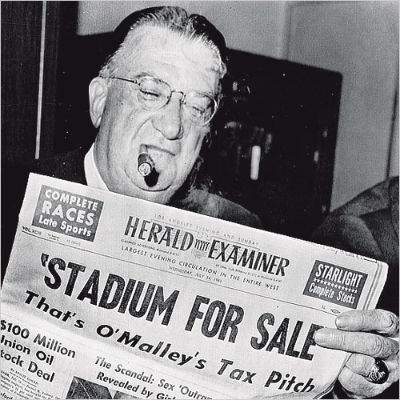

In 1951, Rickey was forced out of the Dodgers organization in a power move by the other owners. Rickey’s replacement was Walter O’Malley who, in Robinson’s words, was “viciously antagonistic.” Robinson relates one time when O’Malley told him that he “had no right to complain about being assigned to a separate hotel. A separate hotel had been good enough for me in 1947, hadn’t it?” In 1951, Rickey was forced out of the Dodgers organization in a power move by the other owners. Rickey’s replacement was Walter O’Malley who, in Robinson’s words, was “viciously antagonistic.” Robinson relates one time when O’Malley told him that he “had no right to complain about being assigned to a separate hotel. A separate hotel had been good enough for me in 1947, hadn’t it?”

In 1953, Robinson appeared on a TV show and, in response to a question, accused the Yankees, still lily-white at the time, of discriminating against Black players. This set off an explosion in the press. Robinson was accused of being a “soap box orator” and a “rabble-rouser.”

Robinson’s fights weren’t always about baseball. In 1954, after the Supreme Court ordered the nation’s schools to be integrated, there was a wave of church bombings in the South. Robinson caught flack for telling a group of reporters that “people who would bomb a church had to be sick and that our federal government ought to use every resource to prosecute them.”

Another time, there was a hullabaloo in the press about the trouble Robinson and his family were having trying to buy a house in Connecticut.

Perhaps most ironic of Robinson’s troubles was an incident that happened in 1949, shortly after Robinson's testimony before HUAC. On September 4, Robeson sung at an open-air concert in Peekskill, in New York’s Westchester County. At the concert, Robeson had been under heavy guard by trade union allies, because the week before a racist mob, armed with baseball bats and rocks, had prevented a Robeson concert in Peekskill.

At the Peekskill concert at which Robeson sung, a sniper’s nest was discovered in the hills overlooking the concert area. The occupants had been disarmed and run off. The concert then went off without problems, but as the concertgoers left they were attacked by the mobs once again, this time under the clear protection of state and local police.

The windows of cars and busses were shattered and much blood flowed — the blood of men, women, and children. At one point, the state police charged a group of concertgoers, guns drawn and clubs flailing, but were fought off. Miraculously, nobody was killed. The windows of cars and busses were shattered and much blood flowed — the blood of men, women, and children. At one point, the state police charged a group of concertgoers, guns drawn and clubs flailing, but were fought off. Miraculously, nobody was killed.

As Bill Mardo, the sportswriter for the Daily Worker at the time, relates, “I remember rushing to Ebbets Field the morning after the Peekskill bloodbath and actually breaking the news to Jackie as he sat in the Dodger dugout a few minutes before gametime...

“Reading the newspaper accounts of the symbolic lynching of Robeson at Peekskill, Jackie Robinson slowly lifted his eyes from the newspapers I had handed him and, anger written all over his face, told me:

“ ‘Paul Robeson should have the right to sing, speak, or do anything he wants to. Those mobs make it tough on everyone. It's Robeson's right to do or be or say as he believes. They say here in America you're allowed to be whatever you want. I think those rioters ought to be investigated, and let's find out if what they did is supposed to be the democratic way of doing things.’

“And then, Jackie, clearly opposed to communism, nailed the insanity of those days right where it lived. ‘Anything progressive is called communism,’ he sighed.

“Let me add that the very same newspapers that had salivated over Jackie's political difference with Robeson at the House hearings... somehow missed Jackie's passionate defense of Robeson's rights just five weeks later! How they missed this Daily Worker front-page exclusive [August 29, 1949] is something to think about.

“But one thing is certain. Jackie Robinson didn't miss spotting the lynch rope at Peekskill... didn't miss seeing the white sheets at Peekskill.”

In 1953, Robeson wrote an Open Letter to Robinson. “I notice… that some folks think you’re too outspoken. Certainly not many of our folks share that view… Maybe those protests around you, Jackie, explain a lot of things about people trying to shut up those of us who speak out in many other fields…

“The same kind of people who don’t want you to point up injustices to your folks, the same people who think you ought to stay in your ‘place,’ the same people who want to shut you up — want to shut up any one of us who speaks out for our full equality, for all of our rights. That’s the heart of what I said in Paris in 1949.”

LIFE AFTER BASEBALL: CIVIL RIGHTS AND POLITICS

When Robinson retired from the Dodgers after the 1956 season, he was done with baseball or, more accurately, baseball was done with him, except as legend. No team offered him a job as a coach or even in the front office. Such positions were still not open to Black men, especially not to Black men like Robinson. Despite turning the other cheek at the beginning of his career, he had become too outspoken, too militant — too Black — to continue getting a check from the magnates.

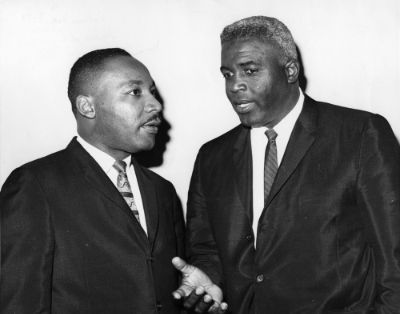

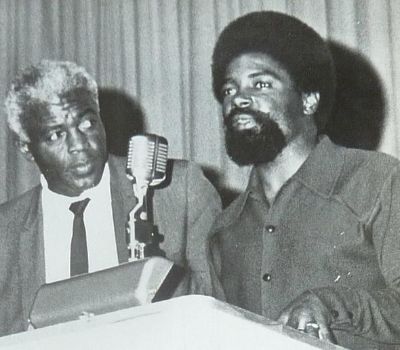

Robinson became very active politically once baseball was behind him. He worked with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), particularly as a fundraiser. He also worked with Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and Jesse Jackson’s People United to Save Humanity (Operation PUSH), making many speeches and appearances in support of the growing civil rights movement. Robinson became very active politically once baseball was behind him. He worked with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), particularly as a fundraiser. He also worked with Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and Jesse Jackson’s People United to Save Humanity (Operation PUSH), making many speeches and appearances in support of the growing civil rights movement.

Despite his active support for civil rights, in 1960 Robinson campaigned for Richard Nixon in his battle with John Kennedy for the presidency, a decision Robinson later acknowledged was not “one of my finer ones.” Ironically, Nixon had been a member of HUAC when Robinson testified before the committee in 1949, although Nixon wasn’t present for Robinson’s testimony. Despite his active support for civil rights, in 1960 Robinson campaigned for Richard Nixon in his battle with John Kennedy for the presidency, a decision Robinson later acknowledged was not “one of my finer ones.” Ironically, Nixon had been a member of HUAC when Robinson testified before the committee in 1949, although Nixon wasn’t present for Robinson’s testimony.

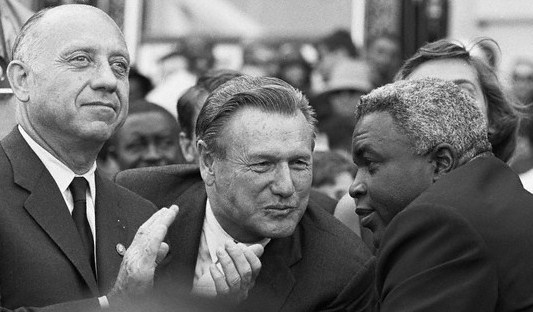

In 1964, Robinson worked actively for Nelson Rockefeller in his primary campaign for the Republican nomination for president. That was the year Barry Goldwater won the nomination. Robinson was appalled by the conduct of Goldwater’s supporters at the convention in San Francisco, and subsequently campaigned for Lyndon Johnson.

In 1966, Robinson went to work for Nelson Rockefeller as a Special Assistant to the Governor for Community Affairs. He quit that post in 1968 in order to campaign for Hubert Humphrey for president, against his former ally Nixon. In 1966, Robinson went to work for Nelson Rockefeller as a Special Assistant to the Governor for Community Affairs. He quit that post in 1968 in order to campaign for Hubert Humphrey for president, against his former ally Nixon.

Although Robinson worked with and for Martin Luther King, Jr., he disagreed “with the stand Dr. Martin Luther King took on the war” in Vietnam and “didn’t like…anti-war demonstrations.” As a supporter of the war in Vietnam, he felt that unity between the civil rights movement and the peace movement would be a “disastrous alliance.” Although Robinson worked with and for Martin Luther King, Jr., he disagreed “with the stand Dr. Martin Luther King took on the war” in Vietnam and “didn’t like…anti-war demonstrations.” As a supporter of the war in Vietnam, he felt that unity between the civil rights movement and the peace movement would be a “disastrous alliance.”

Oddly, however, Robinson felt that although he worked with King, “I never would have made a good soldier in Martin’s army. My reflexes aren’t conditioned to accept nonviolence in the face of violence-provoking attacks.”

ROBINSON: “I NEVER HAD IT MADE”

Robinson’s politics did not conform to anybody’s stereotype.

In 1972, Robinson published his autobiography, I Never Had It Made. This was also the year he died, way too young, at the age of 53, from a heart attack complicated by diabetes. His autobiography reveals that his politics were continuing to evolve. Where he would have gone if he had lived longer will remain a mystery. But his book reveals much about where he was going.

He wrote, for example, about a “dangerous confrontation with a white policeman in the lobby of the Apollo Theater recently. It was a day soon after a couple of police officers had been killed in Harlem… On my way into the lobby, an officer, a plainclothesman, accosted me. He asked me roughly where I was going, and I asked what the hell business it was of his. He grabbed me and spectators passing by told me later that he had pulled out his gun. I was so angry at his grabbing me and so busy telling him he’d better get his hands off me that I didn’t remember seeing the gun. By this time people had started crowding around, excitedly telling him my name, and he backed off. Thinking over that incident, it horrifies me to realize what might have happened if I had been just another citizen of Harlem.”

Although Robinson had been bitterly opposed to Malcolm X’s politics, especially during Malcolm's association with the Nation of Islam, here is what Robinson says in his autobiography: Although Robinson had been bitterly opposed to Malcolm X’s politics, especially during Malcolm's association with the Nation of Islam, here is what Robinson says in his autobiography:

“People have asked me, ‘Jack, what’s your beef? You’ve got it made.’

“I’m grateful for all the breaks and honors and opportunities I’ve had, but I always believe I won’t have it made until the humblest black kid in the most remote backwoods of America has it made…

“…till every man can rent and lease and buy according to his money and his desires; until every child can have an equal opportunity in youth and manhood; until hunger is not only immoral but illegal; until hatred is recognized as a disease, a scourge, an epidemic, and treated as such; until racism and sexism and narcotics are conquered and until every man can vote and any man can be elected if he qualifies — until that day Jackie Robinson and no one else can say he has it made…

“I disagreed with Malcolm vigorously in many areas during his earlier days, but I certainly agreed with him when he said, ‘Don’t tell me about progress the black man has made. You don’t stick a knife ten inches in my back, pull it out three or four, then tell me I’m making progress.’”

One wound Robinson felt keenly was his troubled relationship with his first-born son, Jackie Robinson, Jr. Estranged from his father, Jackie, Jr. volunteered for the Army in 1964. He was shipped to Vietnam and into combat. Robinson supported the war and had, of course, famously testified before HUAC that Blacks should fight for their country. One wound Robinson felt keenly was his troubled relationship with his first-born son, Jackie Robinson, Jr. Estranged from his father, Jackie, Jr. volunteered for the Army in 1964. He was shipped to Vietnam and into combat. Robinson supported the war and had, of course, famously testified before HUAC that Blacks should fight for their country.

But in 1967, Jackie, Jr. was discharged, and came home a drug addict. Before long he was arrested on charges of possession and carrying a concealed weapon. Jackie, Jr. struck a deal allowing him to go into a rehabilitation program in order to avoid a prison sentence. He successfully broke his drug habit and then became a respected counselor with the rehabilitation program that had helped him. But in 1967, Jackie, Jr. was discharged, and came home a drug addict. Before long he was arrested on charges of possession and carrying a concealed weapon. Jackie, Jr. struck a deal allowing him to go into a rehabilitation program in order to avoid a prison sentence. He successfully broke his drug habit and then became a respected counselor with the rehabilitation program that had helped him.

Yet tragedy struck again when he was killed in a solo car accident in 1971.

Robinson, who had previously criticized King’s antiwar politics, probably had his son in mind when he wrote in his autobiography:

“I cannot bitterly oppose…[King’s] notion that America leads the world in violence… I feel that the regime we are supporting in South Vietnam is corrupt and not representative of the people… I cannot accept the idea of a black supposedly fighting for the principles of freedom and democracy in Vietnam when so little has been accomplished in this country. There was a time when I deeply believed in America. I have become bitterly disillusioned.”

And on Robinson’s HUAC testimony against Robeson: And on Robinson’s HUAC testimony against Robeson:

“In those days I had much more faith in the ultimate justice of the American white man than I have today. I would reject such an invitation if offered now.”

Those are startling words from Robinson, but not as startling as this:

“I guess if I could choose one of the most important moments in my life, I would go back to 1947, in the Yankee Stadium in New York City. It was the opening day of the World Series and I was for the first time playing in the series as a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers team…

“There I was the black grandson of a slave, the son of a black sharecropper, part of a historic occasion, a symbolic hero to my people. The air was sparkling. The sunlight was warm. The band struck up the national anthem. The flag billowed in the wind. It should have been a glorious moment for me as the stirring words of the national anthem poured from the stands…

“Today as I look back on that opening game of my world series, I must tell you that it was Mr. Rickey’s drama and that I was only a principal actor.

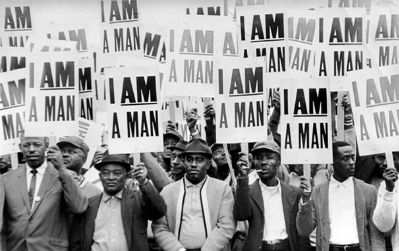

“As I write this twenty years later, I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world. In 1972, in 1947, at my birth in 1919, I know that I never had it made.”

These words are the legacy of a man who is honored every year, and in 42, with elaborate on-field celebrations, including, of course, billowing flags and the singing of the Star Spangled Banner. These words are the legacy of a man who is honored every year, and in 42, with elaborate on-field celebrations, including, of course, billowing flags and the singing of the Star Spangled Banner.

The real movie about Jackie Robinson has yet to be made.

____________________________________________________________________________

ADDITIONAL NOTES

The following are revealing anecdotes that did not make their way into this article.

Carl Erskine, a Dodgers pitcher and teammate of Robinson, tells this story: Carl Erskine, a Dodgers pitcher and teammate of Robinson, tells this story:

“One Saturday afternoon, an article in a newspaper carried a report by a New York Giant scout stating that we were too old. Jackie's too old; Campy's too old. It also said that Erskine can’t win with the garbage he’s throwing. In the game that day, Jackie made a great stop on a ball hit by Willie Mays. It saved a game which turned out to be a no-hitter.

“After the game, Jackie rushed to the Giants’ dugout. With his usual intensity, he took the article out of his back pocket. Pointing to the scout on the Giants’ bench, he waved the article and shouted, ‘How about that garbage?’ ”

Roger Angell tells another story, in his Five Seasons: A Baseball Companion:

"It... happened during an insignificant weekday game between the Giants and the Dodgers back in the nineteen-fifties. Robinson, by then an established star, was playing third base that afternoon, and during the game something happened that drove him suddenly and totally mad. I was sitting close to him, just behind third, but I had no idea what brought on the outburst. It might have been a remark from the stands or from one of the dugouts; it was nothing that happened on the field. Without warning, Robinson began shouting imprecations, obscenities, curses. His voice was piercing, his face distorted with passion. The players on both teams looked at each other, uncomprehending. The Giants' third-base coach walked over to murmur a question, and Robinson directed his screams at him. The umpire at third did the same thing, and then turned away with a puzzled, embarrassed shrug. In time, the outburst stopped and the game went on. It had been nothing, a moment's aberration, but it seemed to suggest what can happen to a man who has been used, who has been made into a symbol and a public sacrifice."

Angell goes on. "The moment became an event -- something to remember along with the innumerable triumphs and the joys and the sense of pride and redress that Jackie Robinson brought to us all back then. After that moment, I knew that we had asked him to do too much for us. None of it -- probably not a day of it -- was ever easy from him"

This story says volumes about what Robinson had to endure. Robinson took more abuse than anybody should have to take. But I don't think that it was "too much" for him. Instead, it is "too much for us" to expect our heroes and leaders to be perfect, anymore than we expect it of ourselves.

Robinson's son, David Robinson, wrote a piece called "The Baptism," which he read at the funeral of his brother Jackie, Jr. Robinson quotes it in his autobiography, "as an epitaph for Jackie," but it could just as well be about Robinson himself:

"And he climbed high on the cliffs above the sea and stripped bare his shoulders and raised his arms to the water, crying: 'I am a man. I live and breathe and bleed as a man. Give me my freedom…'

"When the people saw him they scorned him for his naked shoulders and wild eyes and again he cried: 'I am a man and I seek the means of my freedom.'

"But the people laughed at him, saying, 'We see no chains on your arms, no weight on your feet. Go! You are free…' And they called him mad and drove him from their village. His soul wept, for it knew the weight of chains, and tears fell like tiny stones into the well of his loneliness, and his heart was as empty as a giant hall is empty after a feast.

"And the man journeyed on until he came to the banks of a stream, and… he saw the beauty in the water… and he laughed for he felt the strength of the stream flowing throwing his veins, and he cried: 'I am a man' and the majesty of his voice echoed off the mountaintops and was heard above the roar of the sea and the howl of the wind, and he was free."

Nan Birmingham wrote about a chance encounter with Robinson and his wife on an airplane in the late 1960s ("Lady, That's Jackie Robinson!" in The Jackie Robinson Reader, cited below):

"He was explosive on the field," Rachel [Robinson] said, "and reporters used to ask if he was explosive at home. Of course he wasn’t… There was one clue to when he was upset… He'd go out on the lawn with a bucket of golf balls and take his driver and one after another hit those golf balls into the water."

Robinson sat up. His eyes grew merry. "The golf balls were white," he said.

In his autobiography, In his autobiography,

Robinson tells a story about Floyd Patterson, the renowned Black boxing champion, on a trip to Mississippi: "In plain sight of the press and some very uptight Southern rednecks, Floyd sampled water at two fountains – one marked 'for colored' and one 'for white,' and observed loudly:

"Don’t taste no different to me."

____________________________________________________________________________

BIBLIOGRAPHY

There has been a great deal written about Jackie Robinson.

This is a list of sources that were most helpful to me in putting together this article.

Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives

Hearings Regarding Communist Infiltration of Minority Groups

Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1949

Baldwin, James

Notes of a Native Son

This essay was first published in the November 1955 issue of Harper’s Magazine.

It is also included in the anthology titled Notes of a Native Son,

published by Beacon Press (Boston, MA), in 1955.

Dorinson, Joseph and Joram Warmund

Jackie Robinson: Race, Sports, and the American Dream

Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1998

Foner, Philip S.

Paul Robeson Speaks

New York, NY: Citadel Press, 1978

Harris, Mark

“Where’ve You Gone, Jackie Robinson?”

The Nation: May 15, 1995

Lester, Larry

“Can You Read, Judge Landis?”

Black Ball: Fall 2008

Rampersad, Arnold

Jackie Robinson, A Biography

New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997

Robeson Jr., Paul

The Undiscovered Paul Robeson: An Artist’s Journey, 1898-1939

New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 2001

Robeson Jr., Paul

The Undiscovered Paul Robeson: Quest for Freedom, 1939-1976

Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010

Robinson, Jackie & Alfred Duckett

I Never Had It Made

New York, NY: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1972

Silber, Irwin

Press Box Red: The Story of Lester Rodney,

the Communist Who Helped Break the Color Line in American Sports

Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2003

Tygiel, Jules (editor)

The Jackie Robinson Reader

New York, NY: Penguin, 1997

Tygiel, Jules

Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy

New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1983

|